CNC Machine Accuracy: Tolerance, Repeatability, And Calibration

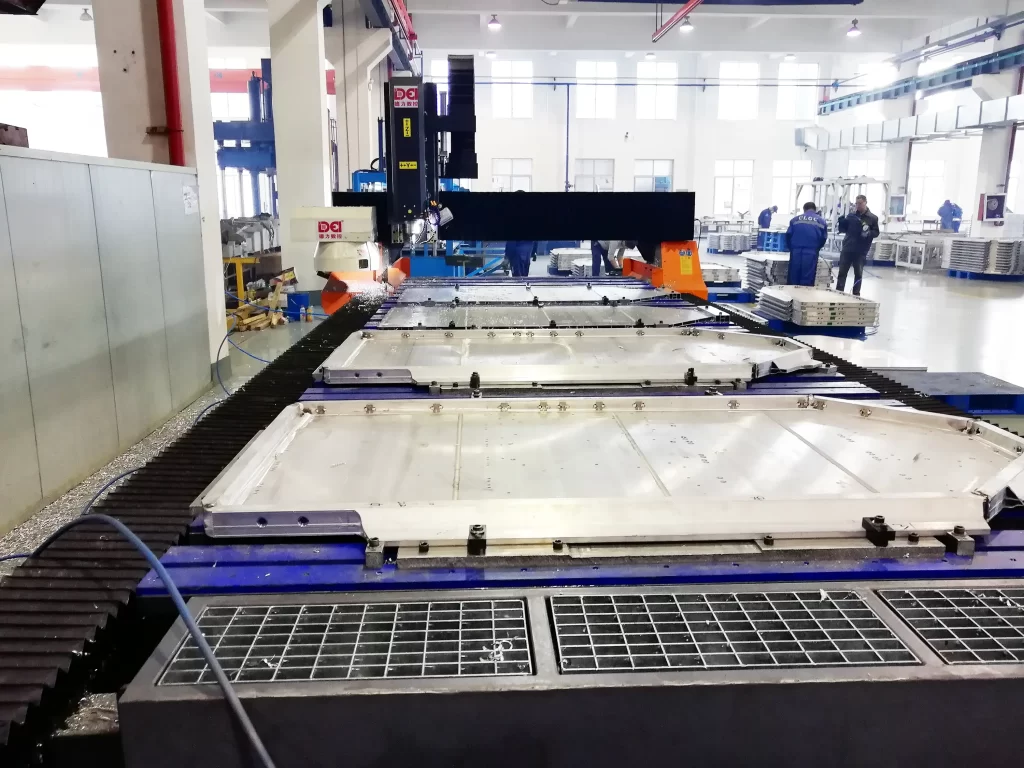

In today’s precision manufacturing landscape, CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines are the backbone of high-consistency, high-efficiency, and high-complexity part production. From aerospace turbine blades and medical implants to critical automotive powertrain components, the quality of these parts hinges largely on the accuracy performance of the CNC machine. Yet, the term “accuracy” is often reduced to a single, oversimplified number—leading to misinformed purchasing decisions, flawed process planning, and inconsistent quality control.

1. The Core Components of Accuracy: Positioning Accuracy, Repeatability, and Geometric Accuracy

1.1 Positioning Accuracy: How Close Is “Close Enough”?

Positioning accuracy refers to the maximum deviation between a machine’s commanded position and its actual physical location. In essence, it answers the question: Can the machine reliably go where it’s told to go?

Per ISO 230-2 (“Test Code for Machine Tools – Part 2: Determination of Accuracy and Repeatability of Numerical Control Axes”), positioning accuracy is typically measured using a laser interferometer across the full travel range, with bidirectional readings taken at evenly spaced intervals. For example, if a vertical machining center shows deviations of +8.2 µm and –6.5 µm over a 500 mm X-axis stroke, its positioning accuracy would be reported as ±8.2 µm.

However, this figure is highly context-dependent. Key influencing factors include:

- Mechanical imperfections: such as lead screw pitch errors or misaligned linear guides;

- Thermal expansion: a 10°C temperature rise in the spindle after one hour of operation can cause Z-axis thermal growth of 15–20 µm;

- Control system latency: servo response delays become pronounced at high feed rates.

Thus, a manufacturer’s claim of “±5 µm accuracy” is meaningless without details on test conditions—ambient temperature, warm-up time, and compliance with recognized standards.

1.2 Repeatability: The True Measure of Stability

Repeatability—often called repeatability or repeatability precision—measures how consistently a machine returns to the same target position under identical conditions. It answers: Can it hit the same spot every time?

According to ISO 230-2, repeatability is defined as six times the standard deviation (±3σ) of seven consecutive unidirectional approaches to a single point. For instance, if the standard deviation of seven X=200 mm approaches is 0.8 µm, repeatability is ±4.8 µm.

In high-volume production, robotic integration, or automated loading scenarios, repeatability often matters more than absolute positioning accuracy. Why? Because consistent starting points allow systematic offsets (e.g., via G54 work coordinate systems) to compensate for any fixed bias—ensuring part-to-part consistency even if the machine isn’t perfectly “on target.”

Key factors affecting repeatability:

- Backlash: mechanical play between the ball screw and nut (should ideally be ≤3 µm);

- Servo stability: low encoder resolution or poorly tuned PID loops can cause micro-oscillations;

- Environmental disturbances: vibrations, drafts, or temperature swings introduce random noise.

1.3 Geometric Accuracy: The Foundation of Performance

Geometric accuracy encompasses all static form and alignment errors—straightness of axes, perpendicularity between axes, spindle runout (radial and axial), and table flatness. These are inherent, systemic errors that cannot be fully corrected through software alone.

Manufacturers typically verify geometric accuracy during final assembly using precision instruments like electronic levels, laser trackers, or autocollimators, producing a formal Geometric Accuracy Inspection Report. Buyers should scrutinize critical specs during acceptance—e.g., “spindle face runout ≤2 µm”—to ensure contractual compliance.

2. Tolerance: Where Accuracy Meets Real-World Requirements

2.1 Tolerance Is the Design Intent; Accuracy Is the Execution Capability

Tolerance defines the allowable variation in a part’s dimensions, form, or position—as specified on engineering drawings. For example, a hole labeled Φ25H7 (+0.021/0) must measure between 25.000 mm and 25.021 mm.

A CNC machine’s capability must comfortably exceed this requirement. As a rule of thumb, the machine’s effective process capability should be 3 to 5 times tighter than the tolerance band. To reliably hold a ±0.01 mm (total 0.02 mm) tolerance, the machine’s stable machining performance should achieve ±0.003–0.004 mm (Cp ≥ 1.33).

But here’s the catch: actual machining accuracy ≠ machine specification. Real-world results are also shaped by:

- Tool wear: a carbide end mill may lose 10–20 µm in diameter after 500 minutes of steel cutting;

- Workholding errors: uneven clamping force can distort thin-walled parts;

- Cutting-induced deflection: elastic deformation during machining may cause spring-back after unclamping.

Hence, trial cuts under production-like conditions are essential—paper specs alone won’t reveal true capability.

2.2 Key Technical Enablers of Tight Tolerances

(1) Structural Rigidity The stiffness of the bed, column, and spindle housing directly affects resistance to cutting forces. High-rigidity designs use dense cast iron (e.g., HT300+) with optimized ribbing. Under a 5,000 N cutting load, a machine with 150 N/µm stiffness deflects ~33 µm—while one at 300 N/µm deflects only ~17 µm, making micron-level tolerances far more achievable.

(2) Feed System Precision Most CNC machines use ball-screw-driven axes. Screw accuracy classes matter: C3 grade offers ±12 µm over 300 mm; C5 is ±18 µm. High-end machines use linear motors—eliminating mechanical backlash entirely and achieving resolutions down to 0.01 µm.

(3) Control System & Interpolation Algorithms Modern CNCs support nanometer-level interpolation (e.g., 1 nm command resolution) and look-ahead functionality, which smooths acceleration/deceleration around corners to prevent over- or under-cutting. For instance, insufficient look-ahead during a R5 mm corner cut can cause contour errors of 5–10 µm.

Equally critical is the proper application of fundamental machining formulas—spindle speed, cutting speed, and feed rate—especially when machining stainless steel or other challenging materials. Optimal parameters balance tool life, surface finish, and dimensional stability.

3. Repeatability: The Lifeline of Mass Production

3.1 Why Repeatability Often Trumps Absolute Accuracy

In volume manufacturing, parts are typically fixtured using zero-point systems (e.g., HSK, Röhm modules). As long as the machine returns to the same program origin consistently, part quality remains stable—even if the entire setup is offset by +10 µm (which can be compensated once in the work coordinate system).

Conversely, poor repeatability (e.g., ±5 µm scatter) causes unpredictable part variation, slashing yield. Statistical Process Control (SPC) shows that when repeatability exceeds 1/6 of the tolerance band, the process capability index (Cpk) drops below 1.0—indicating an unstable, out-of-control process.

3.2 Testing and Interpreting Repeatability Data

Per ISO 230-2, standard testing involves:

- Selecting 5 points across the axis travel (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%);

- Making 7 unidirectional approaches to each point;

- Calculating repeatability as R = 6 × standard deviation per point;

- Reporting the worst-case R as the axis repeatability.

Typical industrial VMCs achieve ±2–5 µm; high-precision models reach ±1 µm or better. For real-world relevance, bidirectional repeatability (which includes backlash effects) is more informative than unidirectional tests.

3.3 Engineering Strategies to Enhance Repeatability

- Preloaded ball screws: eliminate axial play (but increase friction and heat);

- Full closed-loop control: adding linear scales at the table provides real-time feedback, improving repeatability by 30–50%;

- Temperature-controlled environments: maintaining ambient temperature within ±1°C minimizes thermal drift;

- Proactive maintenance: consistent lubrication prevents friction fluctuations that destabilize servo response.

4. Calibration: Sustaining Precision Over Time

4.1 Calibration ≠ Adjustment—It’s Systematic Error Correction

Calibration uses high-precision metrology to measure a machine’s actual kinematic errors and then applies compensation data within the CNC controller. This is distinct from routine tool setting or part alignment—it targets the machine’s intrinsic systematic deviations.

Common compensation types include:

- Pitch Error Compensation (PEC): corrects lead screw manufacturing errors;

- Backlash compensation: offsets directional reversal delays;

- Squareness compensation: fixes X⊥Y or other inter-axis misalignments;

- Thermal error compensation: uses temperature sensors and predictive models to counteract heat-induced drift.

4.2 Calibration Tools and Their Roles

| TOOL | MEASURES | ACCURACY | TYPICAL USE CASE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Interferometer | Positioning, straightness, squareness | ±0.5 ppm | Acceptance testing, annual calibration |

| Ballbar | Circular deviation, servo matching | ±0.1 µm | Quick dynamic performance check |

| Electronic Level | Bed levelness, guide straightness | ±0.01 mm/m | Initial installation |

| Dial Indicator + Test Bar | Spindle runout, axial play | ±1 µm | Routine operator checks |

For example, applying PEC data from a laser interferometer (collected every 10 mm over a 500 mm X-axis) can improve positioning accuracy from ±8 µm to ±2 µm.

4.3 Calibration Frequency and Triggers

- Initial calibration: within 72 hours of installation to verify no damage occurred during shipping;

- Scheduled calibration: every 6–12 months, or before critical production runs;

- Event-driven calibration: triggered by:

- Sudden dimensional shifts (after ruling out tools/programs);

- Mechanical impacts or severe vibrations;

- Prolonged exposure to non-standard temperatures (e.g., uncooled summer workshops).

Maintain calibration records to track accuracy degradation trends—a key input for predictive maintenance and capital replacement planning.

5. From a Procurement Perspective: How to Assess Real-World CNC Accuracy

5.1 Beware of “Paper Specs”

Vendors often advertise “±3 µm positioning accuracy” without clarifying:

- Testing standard (ISO 230-2? GB/T 17421.2?);

- Measurement equipment and calibration certificates;

- Whether compensation (e.g., PEC) was enabled.

Always request full test documentation—including raw data and compensation status.

5.2 Essential On-Site Validation

(1) Document Review

- Factory geometric accuracy report;

- Laser interferometer test logs with plots;

- Third-party certification (if available).

(2) Trial Cut Validation Run a representative test part featuring:

- Positional tolerance on multiple holes (tests repeatability);

- Thin walls (tests rigidity and vibration control);

- 3D contours (tests interpolation fidelity);

- Small or deep features (tests spindle stability).

Post-process, inspect with a CMM (Coordinate Measuring Machine) and calculate Cp/Cpk. A Cpk ≥ 1.33 confirms the machine can sustain production-quality output.

Also, request a First Article Inspection (FAI) report template to ensure future batch traceability. For high-stakes industries, access to CMM inspection services should be part of your supplier evaluation.

5.3 Think Beyond Purchase Price: Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

High-accuracy machines demand higher operational investment:

- Tighter environmental controls (±1°C vs. ±3°C);

- More frequent calibration;

- Specialized lubrication and filtration.

Smart procurement shifts focus from upfront cost to lifetime value—weighing precision-driven quality gains against ongoing maintenance expenses.

6. Conclusion: Accuracy Is a Dynamic Capability, Not a Static Spec

CNC machine accuracy isn’t a fixed number stamped at the factory—it’s a dynamic capability shaped by mechanical health, environmental stability, control sophistication, and maintenance discipline. A top-tier machine can lose 30% of its precision within a year without proper care, while a mid-range system, managed rigorously, can consistently deliver high-accuracy results.

For procurement professionals, grasping the interplay among tolerance, repeatability, and calibration isn’t just technical—it’s strategic. It prevents costly mismatches between machine claims and real-world performance and lays the groundwork for data-driven asset management.

Looking ahead, with smart sensors, digital twins, and predictive maintenance, CNC accuracy management is evolving from reactive correction to proactive preservation—bringing us closer to the ultimate manufacturing ideal: what you design is what you get, and what you program is what you produce.